By the William Durkin Associates team

With so-called anniversary compulsion commonly experienced when five-year increments in the lives of people, marriages, and organizations occur, it is timely to consider the early history of The Giving Institute as it celebrates its 80th anniversary this year.

Whether deliberate or coincidental, establishment of three related professional associations and enactment of seminal Federal legislation share founding dates in the first third of the 20th century; together, they have made significant contributions to the current state of philanthropy.

Whether deliberate or coincidental, establishment of three related professional associations and enactment of seminal Federal legislation share founding dates in the first third of the 20th century; together, they have made significant contributions to the current state of philanthropy.

In 1913, the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was ratified, permitting Congress to impose a Federal income tax. That same year, representatives from 23 colleges and universities met at Ohio State University to establish the Association of Alumni Secretaries for the purpose of sharing ideas and strategies. At the time, the University of Michigan was recognized as a leader for having one of the oldest alumni associations; members paid annual dues of $1.50. The University of Colorado had an intriguing plan: each graduate was asked to commit $25.00 over five years to underwrite the formation of its new alumni association.

Interestingly, alumni secretaries themselves were unlikely to file Federal income taxes as their average annual salary was $1,500. In fact, less than one percent of the population was taxed because individuals had to earn $3,000 and a family had to earn $4,000 to qualify; even then, their assessed tax was one percent of their income.

In 1917, the War Revenue Act introduced the deduction for charitable contributions. That same year, the American College Public Relations Association was formed. Charitable deduction provisions were intended to offset tax liabilities, particularly as tax rates increased to fund American involvement in the Great War. Non-profit organizations, especially colleges and universities, were intensely concerned about the impact of taxes on wealthy donors.

By 1974, these two pioneering associations merged to become the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, popularly known as CASE.

EARLY DECADES OF THE AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF FUND-RAISING COUNSEL

Although discussions among executive leaders of fundraising consulting firms had occurred over several years, the Social Security Act of 1935 is considered a precipitating factor in the establishment of the American Association of Fund-raising Counsel (AAFRC), the association that, in this century, became The Giving Institute.

While fundraising campaigns in the United States date to the late 19th century, with the Red Cross and YMCA as recognized leaders, the $15 million Harvard University campaign after World War I lead to the establishment of the earliest consulting firms. The crash of 1929 ended capital campaigns as appeals for relief and social services, especially for the elderly, were considered much more compelling.

The Social Security Act of 1935 was initially perceived as a threat to charitable giving. Such concerns were accelerated by remarks that President Franklin Delano Roosevelt made when he signed the bill into law:

At the time, the standard measurement that fundraising consulting firms used to assess trends in philanthropy was the total secured by the 417 Community Chests/United Ways in existence. Between the market crash of 1929 and the enactment of the Social Security Act, that trend reflected a 13% overall decline, with the total at $70 million in 1935. As only 75 Community Chests/United Ways had paid staff, service to these annual campaigns was consistent revenue for consulting firms and the threat of further decline was a precipitating factor leading to the founding of AAFRC.

The mid-1930s brought the first canned beer, release of the board game Monopoly, and the first night baseball game. Golfer Tommy Armour, winner of the PGA and U.S. Open championships in 1937, shot 23 on a par 5 hole that same year, a record of ineptitude that still stands for professional golfers.

Initial plans called for 11 founding members of AAFRC and annual dues of $50 for each firm. However, despite follow-up calls, only nine firms – from New York City, Pittsburgh, and Chicago – honored their dues commitment and are now considered the founding firms. Today, Marts & Lundy is the only firm from the initial roster that continues membership although two other firms still exist.By the second year, the bank balance was $566 after having spent $397.

From 1935 to 1954, AAFRC by-laws were unchanged, names of member firms were not identified in literature, and no office or staff was secured. Founded largely on ethical considerations, it was an association that set standards for firms assisting non-profit clients in raising money. These principles were stated in the by-laws:

- Fees are to be based on services provided, not commissions or percentage of funds raised;

- Executive leadership must show at least 6 years continuous experience in fundraising field;

- No firm shall pay officers of philanthropic institutions for their influence in engaging the firm;

- Fees should not be charged in initial meetings with prospective clients.

In the first few years, meetings featured outside speakers, seminars provided by members, and discussions of Association business and standards. One of the earliest meetings celebrated the accumulated campaigns managed by members reaching the million-dollar level in just one year.

By 1938, AAFRC had $1,200 in the bank and members passed a resolution to allow firms to place the emblem and Member of AAFRC on stationery and printed materials. Only a single meeting – in 1943 – was held during World War II, from 1941 – 1945.

The end of World War II brought a huge demand for professional fundraisers as the G.I. Bill created a surge in the capital needs of colleges and universities, hospitals received matching federal funds for contributions toward facility expansion, and social service agencies and churches grew after years of constraint.

In 1948, member firms still paid $50 in annual dues.

RAPID MATURATION BEGINNING IN 1954

In 1954, AAFRC decided to go public with monthly meetings to make decisions about becoming a national association supporting members and philanthropy through a headquarters and professional staff. Members admitted during that year brought the total to 18 firms and 16 additional firms were admitted by 1959.

It was also in this year that AAFRC hired three staff and established headquarters in Manhattan with a $33,500 budget. Fees for members were set at three-fourths of one percent of the previous year’s income. The highest priority was enlistment of new firms until all firms engaged in fundraising within the United States were members. The second priority was becoming the focal point for philanthropic information, and the third priority was overcoming misunderstandings among institutional administrators, Board members, and the general public about ethical fundraising.

In 1955, the AAFRC became incorporated and retained its first Executive Director who earned a salary of $15,000 and was charged with:

- Developing information on philanthropy;

- Broadening membership;

- Being alert to legislative developments;

- Managing a program in public relations;

- Developing an official periodical.

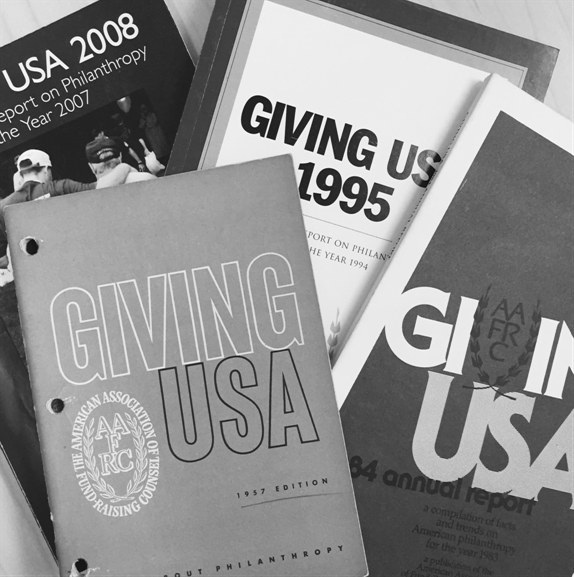

The year 1955 is when 22 year-old Elvis Presley bought Graceland for $100,000 and charitable giving in the United States reached $4 billion; forty years earlier, giving was estimated at $500 million. The AAFRC distributed its first yearbook with 2,000 copies distributed to newspaper editors, public libraries, and organized philanthropies.

A 1957 survey sponsored by AAFRC revealed public views about the fundraising profession:

- There is a dearth of understanding of fundraising;

- There is a lack of recognition of any leaders of professional fundraising;

- There is confusion about semantics of fundraising;

- There is some opposition toward anyone making money from charities;

- There is absolutely no understanding of the basis of fees charged;

- AAFRC and its Code of Ethics are unknown to volunteer leaders in non-profit organizations.

The AAFRC budget increased between 1956 and 1960 from $45,000 to $106,000 with assets of $125,000. There were 31 member firms by 1960 with a combined total of more than 500 employees. In 1964, names and addresses of member firms were published for the first time, the by-laws were amended to increase Board size from 11 to 40, and the 10th anniversary of Giving USA produced 38,000 copies.

So in leaving the 1960s, AAFRC was poised to be a catalytic force in the United States that would have been unimaginable at its founding 25 years earlier.

A significant portion of the information in this article is summarized from “A Beacon for Philanthropy: The American Association of Fund-Raising Counsel Through Fifty Years: 1935 – 1985” by Wolcott D. Street.